Discover the Miaos

A BIT OF HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY

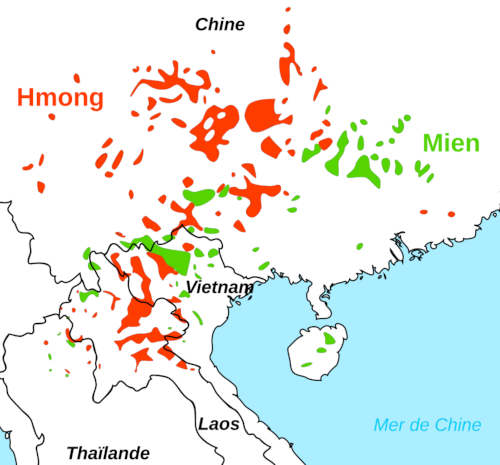

The Miao, with a population of about 9 million, are the fourth largest ethnic minority in China. Their origins date back to ancient times, further north than their current location. Over the centuries, they have been pushed southward by the Han Chinese, gradually settling in Southwest China, mainly in Guizhou (50%), Yunnan, and Guangxi. Their history is marked by major revolts against the central power, some of which, like the Taiping Rebellion in the 19th century, forced the Miao to migrate to Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, and even Thailand, where they are known as Hmong. During this exodus spanning centuries, the Miao divided into small, relatively isolated communities in the mountains, explaining the great diversity of languages and customs that characterize this people. In modern times, the Miao-Hmong have experienced a significant wave of immigration following the Indochina wars, leading them to several continents, resulting in large communities established in France, the United States, and even French Guiana.

TRADITIONS AND A LIVING CULTURE

The Miao are a mountain people who have carved terraces to cultivate glutinous rice, grains, corn, and vegetables. The character that represents them, 苗, combines the roots of grass (艹) and rice fields (田), designating them since ancient times as a people of farmers. Their agriculture is subsistence-based and not mechanizable due to the small sizes of the terraces that hold rice and vegetables, making it difficult to farm. Their totem animal is the water buffalo, to which they pay a genuine cult, and it is not uncommon to find an effigy at the entrance of the village. According to legend, the ancestor of the Miao was a buffalo himself…

Traditionally, the Miao build their homes from wood, with the ground floor reserved for storing agricultural tools and raising pigs, chickens, and sometimes cows, while the first floor serves as the family's living quarters and storage for rice harvests. Although they have long remained isolated from the wave of development in China, in the last 15 years, the Miao have seen their living conditions improve: new road infrastructure has facilitated communication, and many have been able to construct modern homes with kitchens and bathrooms.

Daily meals are always rice-based, often accompanied in summer by stir-fried vegetable and meat dishes cooked in a wok, and in winter, typically by a broth fondue made with poultry in which green leaves or cabbage are dipped. The Miao enjoy strong flavors—sour, spicy, and acidic—and all dishes are spiced with chili. During festivals, celebrations such as weddings or the presentation of newborns, pigs are prepared for communal meals that bring the village together.

A JOYFUL AND FUN-LOVING PEOPLE

The Miao are deeply attached to their culture and history, and the year is filled with lively festivals where they celebrate in traditional costumes. Guizhou is even nicknamed the "land of a hundred festivals" due to the numerous Miao celebrations: New Year, Sisters' Festival, Harvest Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, music festivals, singing competitions... On these occasions, women bring their festive attire out and adorn themselves with kilos of silver jewelry—tiaras, torques, necklaces, earrings, bracelets... passed down from mother to daughter.

The Miao are naturally optimistic and cheerful people; they enjoy laughing, singing, drinking, and celebrating. Among the Miao of Shidong, the Chinese New Year is followed by a month literally named 'Drinking Alcohol' ☺, a period for weddings and visits to extended family where homemade rice wine flows freely, and women showcase their skills in traditional songs celebrating their history.

AN EXCEPTIONAL CRAFTSMANSHIP

For this society without a written language, the embroidery that mainly adorns women's costumes is a testament to their history and culture. This textile art—comprising weaving, embroidery, and batik—has been recognized for centuries, as texts from the beginning of our era already mention fabrics in trade exchanges between the Miao and Han.

Women create their garments from cotton or hemp, dyeing them with indigo to achieve dark blue, black, or even brown hues by adding cattle blood to the indigo. In some sub-groups, the fabric is then pounded with a mallet, giving it a satin-like finish and increasing its durability.

The numerous sub-groups that make up the Miao-Hmong people can be recognized by the costumes and hairstyles of the women, which are almost infinitely rich. The costume can be quite complex, including skirts, leg warmers, aprons, vests, and jackets—all intricately embroidered. The extraordinary variety of motifs and stitches used reflects the wealth of their art.

Men, on the other hand, have a tradition and expertise in jewelry-making, recognized even by distant Chinese emperors. Silver adornments possess protective qualities but also symbolize the wealth and social status of the family. Traditional jewelry-making techniques are varied, including filigree, hammering, and engraving, but all remain deeply artisanal and without modern tools. Many old jewelry pieces were often made by melting down silver coins that circulated for a long time in China.

STORIES, LEGENDS, AND SYMBOLS: THE BUTTERFLY

Essential in Miao culture and recurring in their embroidery and jewelry, the butterfly refers to the founding myth, which has several variations of the Butterfly Mother, born from a tree that laid 12 eggs. From these eggs, long incubated by a mythical bird, were born the first man, thunder, the dragon, the tiger, the buffalo, and several other animals.

THE PHOENIX

A mythical symbol of rebirth and the cycles of life and death, the phoenix is often depicted on Miao baby carriers. A protector and bearer of luck, it holds an eminent place among the Miao, even lending its name to a city, Fenghuang. Associated with and opposed to the dragon, the phoenix represents the feminine aspect of the Yin-Yang couple. The Miao often use the allegory of Dragon/Phoenix in their representation of this creative duality of Yin and Yang.

THE DRAGON

Also born from the 12 eggs of the Miao butterfly mother and thus a brother to humans, the dragon is central to Asian culture. Unlike our dragons, it does not breathe fire but fertilizes the earth with rain, symbolizing protection, luck, and prosperity, though it can also be dangerous like the water to which it is intimately linked. Frequently present in Miao iconography, it is often associated with the phoenix, serving as the male counterpart of Yin/Yang.

THE BIRD

Not necessarily a phoenix—distinguished by its oversized tail—it is often represented in pairs. Considered by shamans to be a link between humans and the invisible, in Miao culture, it symbolizes fidelity and marital happiness. It also recalls the founding myth of the butterfly mother, whose eggs were incubated by a bird.

THE FLOWER

In all its forms and sometimes stylized to the point of being unrecognizable, the flower is very present in the embroidery. It celebrates beauty and harmony and pays tribute to the vitality of nature.

THE BUFFALO

Often represented by its horns, which give the Miao their name "horns" due to the traditional hairstyles of women, it symbolizes both ancestor worship and celebrates this animal, indispensable to the ancestral rice culture.